[ad_1]

Shannon Stapleton / Reuters

WASHINGTON — Eric Munchel was photographed inside the Capitol on Jan. 6 wearing tactical gear and carrying plastic zip-tie handcuffs, one of many images that day that raised questions the FBI is probing about how thoroughly some insurrectionists planned for violence and what they hoped to do. He was arrested on Jan. 16. A week later, a judge in Tennessee ruled he could go home pending trial.

Prosecutors had argued to keep Munchel — one of the few defendants to face a felony conspiracy charge so far, along with his mother — in custody. They noted he was also accused of bringing a Taser into the Capitol and was allegedly recorded talking about stashing other weapons nearby. After the Tennessee judge ordered home detention, they raced to stop his release, petitioning a federal judge in Washington, DC, to intervene; they said the FBI found an “arsenal” of 15 firearms at his home and noted that he told a reporter he was prepared to “fight if necessary.” The DC judge agreed to halt Munchel’s release, and he’s still in custody pending another hearing.

“[It] is difficult to fathom a more serious danger to the community — to the District of Columbia, to the country, or to the fabric of American Democracy — than the one posed by armed insurrectionists, including the defendant, who joined in the occupation of the United States Capitol,” prosecutors wrote in a Jan. 24 brief.

Win Mcnamee / Getty Images

Prosecutors allege this is Eric Munchel, carrying zip-tie handcuffs in the US Senate chamber.

Munchel’s situation is unusual. Most of the 150-plus people charged in the Capitol insurrection so far have been allowed to go home after their first court appearance; hundreds more who went into the building on Jan. 6 and then were able to leave haven’t been charged yet. The bar is high for pretrial detention — people aren’t supposed to be punished for crimes they haven’t been convicted of yet — and prosecutors are only asking for detention in a small number of cases. Meanwhile, hundreds of people who participated in the assault are going back to their everyday lives as they wait for their day in court, or to be arrested at all.

Judges have agreed with prosecutors in more than two dozen cases to hold defendants because there are no release conditions that would ensure the safety of the community. For an even smaller group that includes Munchel — BuzzFeed News has identified at least seven so far — the government is fighting release orders after losing the first round. Even when judges have ordered home detention, prosecutors have argued it’s not enough to prevent future violence and interference with ongoing investigations, and to ensure defendants show up to court going forward.

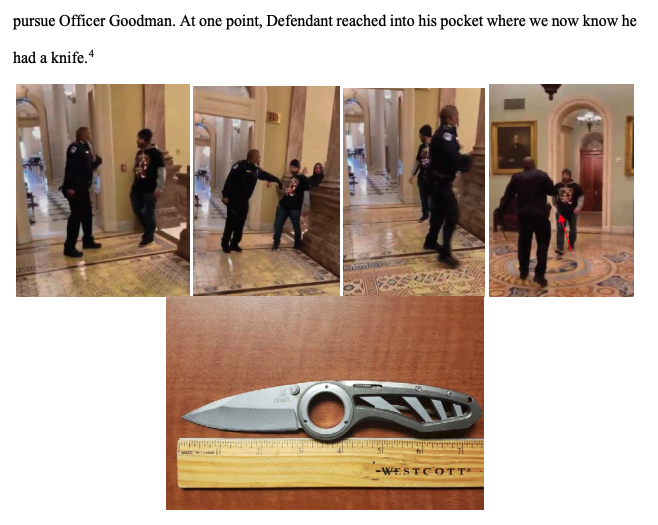

Prosecutors are appealing an Iowa magistrate judge’s decision to order home detention for Douglas Jensen, who was identified in videos and photographs leading a mob that chased US Capitol Police Officer Eugene Goodman inside the Capitol. Prosecutors cited evidence that Jensen was carrying a knife at the time and had a criminal record, as well as his belief in QAnon and his stated desire to participate in a “revolution” and arrest public officials. Releasing Jensen from custody “will only reinforce his belief that his cause is just,” prosecutors wrote in a Jan. 22 brief. A judge in DC agreed to hold Jensen and hasn’t scheduled a hearing yet.

US Department of Justice / Via assets.documentcloud.org

Images that prosecutors say show Douglas Jensen in the Capitol and a knife he had in his pocket

“Defendant’s eagerness to travel more than 1,000 miles in hopes that he would hear President Trump declare martial law, and his willingness to take martial law into his own hands when no such pronouncement came, says more about Defendant’s characteristics than any criminal history ever could,” prosecutors wrote in Jensen’s case.

In another case, a federal magistrate judge in New Jersey denied the government’s request to hold Scott Fairlamb, who is accused of punching a police officer in the head during the riot on the Capitol grounds. According to charging papers, a tipster sent the FBI a video that Fairlamb allegedly recorded and posted on Facebook showing him holding a collapsible baton outside the Capitol and saying, “What patriots do? We fuckin’ disarm them and then we storm fuckin’ the Capitol”; Fairlamb deleted other videos he’d posted going into the Capitol, according to the witness.

The New Jersey judge ordered home detention, which would allow him to only leave his house for work, court, and a few other reasons. Prosecutors immediately appealed to a judge in DC, who agreed to keep Fairlamb in custody and hasn’t set a hearing date yet.

US Department of Justice / Via assets.documentcloud.org

Screenshots in charging papers for Scott Fairlamb

The government won the first of these cases to go before a judge in Washington. Following nearly five hours of witness testimony on Jan. 15, a judge in Arkansas ruled that Richard Barnett, the man photographed in House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s chair who later bragged about leaving a note that read, “Nancy, Bigo was here, you bitch,” could go free. Prosecutors immediately petitioned a judge in DC to intervene, and the judge ordered him jailed on Thursday, saying that his “entitled” behavior showed a “total disregard for the US Constitution.”

Magistrate judges typically handle first court appearances for anyone arrested on federal charges and make decisions every day about whether defendants should be kept in custody. Those decisions can be reviewed, and reversed, by a US district judge. Because police allowed most people to leave the Capitol on Jan. 6, they’re being arrested in their home states and making their first appearances in their local federal court. When prosecutors have wanted to fight a release order, they’ve taken it to a district judge in Washington, where all of these cases ultimately are being prosecuted.

Court records show that being accused of descending on the Capitol to stop Congress from certifying the results of the election isn’t enough on its own for the government to argue that someone should be held behind bars before trial. Prosecutors have been saving these fights for cases that involve weapons, assaults on police officers, specific threats of violence against elected officials, previous criminal convictions, and people who allegedly took a leadership role and urged others to commit violence.

These cases have also forced judges to grapple early on with the thorny question of how much a person’s embrace of online conspiracy theories or even a collective delusion like QAnon makes them such a danger to society that they should be behind bars. Many defendants touted former president Donald Trump and Republicans’ lie that the election was stolen in explaining why they stormed the Capitol, but the government isn’t asking for all of them to remain in custody.

Robert Nickelsberg / Getty Images

Jacob Chansley at the rally before storming the Capitol

On Jan. 15, US Magistrate Judge Deborah Fine in Phoenix granted the government’s request to hold Jacob Chansley, an Arizona man photographed wearing fur and horns in the Senate chamber and a QAnon believer. Fine explained from the bench that Chansley’s “actions and words demonstrate he’s willing to participate in the violent disruption of the work of our government” and that she had no confidence he would follow court orders if released. On Jan. 25, US Magistrate Judge Zia Faruqui in Washington ordered detention for Matthew Miller, a Maryland man accused of deploying a fire extinguisher at police at the Capitol.

“Mr. Miller’s false beliefs regarding the illegitimacy of the current government lead the Court to believe that there are no conditions … that could prevent Mr. Miller from behaving in a similar manner or engaging in another insurrection of this kind,” Faruqui wrote in an order explaining his decision.

Free to go

The handling of the Capitol insurrection arrests contrasts with how police in Washington and other cities have responded to demonstrations that led to mass arrests in the past. People who took to the streets over the summer to protest police brutality and racism often were taken into custody on the spot by the hundreds; police sometimes used a tactic known as “kettling” to surround large groups to make mass arrests. That also happened in Washington during protests against former president Donald Trump during his inauguration in January 2017; hundreds were arrested.

In contrast, the Metropolitan Police Department arrested just over a dozen people at the Capitol on Jan. 6. The US Capitol Police announced 14 arrests that day, and dozens of people were arrested in the evening for violating a curfew order in Washington. That meant the FBI and local law enforcement agencies around the country spent the days and weeks after the insurrection tracking down people captured in videos and photographs that day, or who posted online or spoke to reporters about participating, or who had friends and family members who tipped off investigators.

A common thread running through those earlier mass arrests and the Capitol insurrection cases is that people charged with misdemeanor crimes are often allowed to go free while their cases are pending. Judges are supposed to impose the least restrictive conditions that they believe can protect the community, and in many of the Capitol cases prosecutors have not argued for detention. In most cases, prosecutors and defense lawyers have agreed on a standard set of release conditions that limit when defendants can return to Washington, prohibit them from having illegal firearms, require that they check in with pretrial services every week to make sure they haven’t tried to flee, alert the pretrial services office if they have to leave their state, and need to get the court’s permission to travel internationally.

In a few cases, however, the government has asked for different release conditions, often being cagey about why. The hearings are happening virtually due to the pandemic, meaning anyone with the phone number can listen in. Providing too much information on a public line, prosecutors say, could jeopardize their ongoing investigations. Acting US Attorney Michael Sherwin in Washington has said that they have hundreds of open cases, and that defendants who were already arrested could face additional charges as those investigations continue. Prosecutors could reopen the detention issue if they find new evidence that a defendant is dangerous or a flight risk, or that a defendant has violated any of their release conditions.

For some defendants, the government asked the judge to order the defendant to turn over any firearms or explosives they possess, and bar them from acquiring any new ones. In other cases — like that of Matthew Council, a 49-year-old from Florida accused of breaking into Capitol building and pushing an officer — the judge ordered the defendant to submit to substance abuse testing and any recommended treatment. In several other cases, the judge required mental health evaluations.

A few released defendants are being tracked using GPS devices, like ankle monitors. A judge ordered GPS monitoring for Tim Gionet, known online as Baked Alaska (a former BuzzFeed employee who later became a white supremacist troll), because he had already violated the conditions of release after he was arrested for pepper-spraying a bouncer in Arizona in December. He was barred from traveling outside of Arizona in that previous case, but he traveled to DC, stormed the Capitol building, and was arrested in Houston.

Some defendants considered flight risks or a danger to the government’s investigations have been put under house arrest. Riley June Williams, a 22-year-old from Pennsylvania accused of stealing Nancy Pelosi’s computer and attempting to sell it to Russia (her lawyer says these are the fabrications of a vengeful ex), was released to house arrest with an ankle monitor. According to an FBI affidavit, Williams tried to flee before turning herself in. The prosecutor said in court that she tried to delete social media accounts relevant to the investigation, and encouraged others to delete relevant messages. While under house arrest she is barred from using the internet, except for court-mandated mental health treatment and meetings with her lawyers. Her mother is tasked with enforcing the court’s orders.

Behind bars, for now

In the small but growing number of cases involving detention requests by the government, prosecutors have argued that there simply aren’t any release conditions that would keep the community safe. Federal magistrate judges in Virginia and Ohio agreed to detain Thomas Caldwell, Jessica Watkins, and Donovan Crowl, the three alleged members of the Oath Keepers militia group who are charged with conspiracy and accused of trying to carry out a violent, preplanned attack on the Capitol; a grand jury returned an indictment against those three defendants on Wednesday.

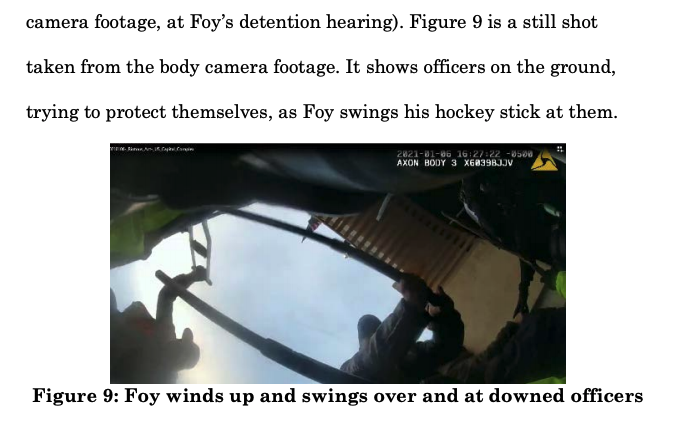

US Department of Justice / Via assets.documentcloud.org

Prosecutors say this screenshot from police body camera footage shows Michael Foy attacking an officer with a hockey stick.

Other cases where judges ordered defendants jailed include those charged with violence against law enforcement, such as Michael Foy, a Michigan man accused of using a hockey stick to assault police officers, and Peter Stager, an Arkansas man accused of using a flagpole to beat an officer on the ground. Some defendants who allegedly posted threats online were also detained, including William Calhoun, a Georgia lawyer whose social media posts included “I have tons of ammo. Gonna use it, too – at the range and on racist democrat communists,” according to court papers, and Garret Miller, a Texas man who responded to a tweet after the riot from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez with “Assassinate AOC.”

US Department of Justice / Via assets.documentcloud.org

Prosecutors included these Twitter screenshots in charging papers for Garret Miller.

A few defendants kept in jail so far are using the release of other Capitol arrestees charged with similar offenses to try to reargue for their own release. A lawyer for Matthew Miller, the Maryland man accused of discharging a fire extinguisher, had argued that he wasn’t accused of assaulting or injuring anyone and compared his client to Williams, the woman accused of stealing Pelosi’s laptop, who was released to house arrest. The judge was not convinced, writing in the detention order that what Miller was accused of was “troubling and extremely dangerous.”

More detention fights are coming. A hearing is scheduled for Feb. 1 in Washington on the government’s motion to keep Couy Griffin, the founder of “Cowboys for Trump,” in custody. In a Jan. 19 court filing, prosecutors argued Griffin was a flight risk and a danger to the community, citing what they described as a pattern of posting threats of violence online and showing a “disdain for lawful authority,” as well as his participation in the insurrection and vow to come back to DC for President Joe Biden’s inauguration. If Griffin had refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of an election certified by Congress, prosecutors wrote, “certainly he would deny the authority of the judicial officers appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.”

“The defendant’s inflammatory conduct, repeated threats, delusional worldview, and access to firearms makes him a danger to the community,” prosecutors wrote.

Griffin’s lawyer filed a brief on Jan. 27 arguing that the First Amendment’s free speech protections barred the judge from taking Griffin’s speech and political views into account. He noted Griffin wasn’t accused of going inside the Capitol building, but rather being on restricted grounds outside. Griffin had guns to protect himself and his family, his lawyer argued, and denounced “disrespect for law enforcement.” The brief cited Williams’ release, as well as other defendants charged in the insurrection who were allowed to go free.

In at least one case, the government is already back in court accusing a defendant who was allowed to go home of violating his release conditions. In the case of John Earle Sullivan, a Utah man who was released to home detention, a pretrial services officer notified the court on Jan. 27 that he’d allegedly violated a condition limiting his internet use on four occasions; the court filing didn’t provide details. The government had unsuccessfully argued before to keep Sullivan in custody. A hearing is set for Feb. 1 on whether the judge should send him back to jail.

[ad_2]

Source link